Oregon Water Pollution CleanUp Plans

Despite the fact that Congress first required the development of TMDL, water pollution cleanup plans, in the 1972 Clean Water Act, in many ways TMDLs remain highly theoretical. Although the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has developed hundreds of TMDLs, they are but a fraction of those remaining to be done. And existing TMDLs suffer from a variety of defects including some that simply contain no limitations on pollution sources, which is the entire point of the process. Worse, TMDLs are treated as irrelevant, by DEQ staff issuing discharge permits and by the agencies that are responsible for controlling nonpoint pollution from sources such as logging and farming.

The TMDL program in this country did not get off the ground until environmentalists began bringing lawsuits just to get them done. Oregon was the first state to be the subject of these lawsuits, after which they came in a wave that swept the country. Oregon’s mostly unproductive entanglement with the TMDL program began in 1986 when, to settle a lawsuit by the Northwest Environmental Defense Center (NEDC), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) signed a consent decree promising that all TMDLs would be developed for the state within five years. At the time, Oregon’s list of impaired waters was exceedingly small, around 15 waterbodies. After the consent decree, Oregon kept its list artificially short in order to lessen the burden of complying with it. Although the list grew steadily over the years, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) balked at producing a list reflective of the state’s actual poor water quality. In 1992, NWEA filed another lawsuit, resulting in Oregon’s 1994-96 list. And, in 1996, NWEA sued EPA again because the federal agency had failed to develop TMDLs in a timely fashion. As a result, EPA was put under a 10-year consent decree to complete a specific number of TMDLs.

That consent decree terminated in 2010. Since that time, Oregon DEQ has developed zero TMDLs. And the state has struggled to update its impaired waters list, which is required every two years, with EPA’s having to step in time after time to complete the list.

Oregon’s Temperature TMDLs: A Travesty

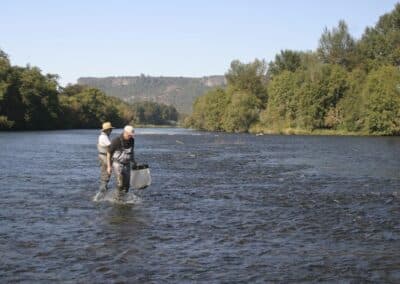

Most of Oregon’s TMDLs have been for temperature, a ubiquitous pollutant that causes grave problems for the states’s many threatened and endangered salmonids—fish that require cold water for survival. Because temperature increases in streams are caused primarily, although not exclusively, by lack of shade and flow and streams becoming more shallow and wide, the TMDLs should result in requirements for forested stream-side buffers to provide shade, increase groundwater flows, and prevent erosion. Instead, they are completely ignored by DEQ and the agencies that regulate or fail to regulate logging and farming.

Even more stunning is how DEQ has developed these temperature TMDLs. Using a rule—since thrown out by a federal court—that allowed Oregon to substitute higher temperatures in place of those that had been determined to protect fish, the DEQ developed its TMDLs to increase allowable temperatures in Oregon waters. These so-called natural conditions set out in the temperature TMDLs ranged as high as 32º C, a temperature that EPA has found causes death to salmon within seconds.

In 2012, NWEA sued EPA for approving these Oregon temperature TMDLs as well as challenging a Willamette River basin mercury TMDL that failed the basic test of TMDLs: to set allowable allocations to pollution sources.

NWEA Seeking Better Uses of TMDLs

In 2010, NWEA settled a lawsuit concerning Oregon’s failure to control polluted runoff in coastal watersheds. The basis of the settlement was Oregon DEQ’s agreement to use TMDLs in those watersheds to address nonpoint source pollution. DEQ agreed to issue a pilot TMDL of this new type—for the MidCoast Basin—that would set out load allocations for nonpoint sources and, in addition, would translate those load allocations into the streamside buffer requirements needed to meet water quality standards in the TMDL. In addition, DEQ agreed to issue those TMDLs as orders to significant nonpoint sources. In the end, DEQ got cold feet and, while continuing to develop this TMDL, abandoned the entire purpose of demonstration project. At the same time, the Oregon Department of Forestry pursued the development of new rules on the number of trees required to be left along streams in western Oregon watersheds. This agency claimed it was aiming its new regulations to allow stream warming of 0.3º C, refusing to acknowledge that some completed TMDLs allocate no warming whatsoever—an allocation of zero—to logging activities.

Related News

Ashland Sewage Permit Comments

Rogue River Court Victory

Cleaning Up the Rogue River: Update